Gabon and Indonesia – OPEC Membership Motivation

In 2009, Indonesia left The Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. Earlier this year (2016), they successfully rejoined, after fewer than seven years apart from the group. Gabon left OPEC in 1995. Earlier in our research, this exit seemed permanent, but in April of this year, they formally reapplied for membership. Alongside Ecuador, who left in 1992 and rejoined in 2007, a distinct trend is beginning to emerge.[1] Notably, Ecuador, Gabon, and Indonesia all fall at the very bottom of OPEC’s list in terms of share of oil reserves.[2] Originally, the intent of this post was to investigate what drove Indonesia to reenter OPEC in contrast to why Gabon chose to remain on the outside. Although Gabon has yet to be readmitted, their application signals a desire for membership, and searching for and understanding this desire has been the purpose of our project all along. With the recent developments mentioned above, this blog will attempt to find a common thread between the shared desire of Indonesia and Gabon to rejoin OPEC.

Background

As both countries have rather small oil reserves compared to those of larger member countries, a basic correlation between the two may be established. That said, these two countries share few common characteristics, which makes a comparison of motivations more interesting. Indonesia is made up of over 17,000 islands and is the world’s fourth largest country by population.[3] Furthermore, Indonesia is the world’s most linguistically diverse country, with over 700 known languages currently spoken by its citizens. Indonesia also has the world’s highest population of Muslims, which stands in stark contrast to Gabon’s heavily Christian population.[4][5]

Conversely, Gabon is one of the world’s least populated countries, with under two million citizens.[6] With valuable natural resources and a small population, Gabon has a GDP per capita of almost $19,000, a number far greater than the just over $11,000 held by the population of Indonesia.[7] Despite this gap, the unemployment rate in Gabon is over 20% – four times higher than that of Indonesia.[8] Gabon and Indonesia are both presidential republics with a powerful president, bicameral legislature, and a judicial branch headed by a supreme court.[9]

Why They Left

An examination of why Gabon and Indonesia chose to reapply for membership would be incomplete without first understanding each country’s different reasons for leaving.

Indonesia’s official account of their decision to leave OPEC tells the story of a country not producing enough oil to be a net exporter or “deserve” membership. As the government stated their intention of boosting oil production, this explanation is consistent with the narrative of a country attempting to cut their obligations until such a time as they have enough clout to truly participate in the organization.[10] It has been suggested that Indonesia was simply displeased with how much weight they had in discussions, despite paying the millions in yearly membership fees required of all OPEC countries. With little to bring to the table, the fees would have been cumbersome and likely caused the country’s leaders to question whether membership was worth the cost.[11] The fact that OPEC did not even publically comment on the withdrawal of Indonesia lends credence to the argument that the country had little influence and therefore little to gain.[12]

An alternative story to one of high fees and low clout delves into domestic politics. As oil prices were reaching their all-time highs in 2008, Indonesia found itself unable to sustain the level of oil subsidies they had previously maintained in their efforts to keep domestic prices low. At the time, Indonesia was the only net importer of oil amongst all OPEC member countries, meaning that lower oil prices would leave the country better off by setting it apart from the hopes of the rest of the organization.[13] When the government raised oil prices in response to the international market, the population was hit hard.[14] Protests erupted across the country, with many demanding the return of subsidized prices.[15] As a net importer of oil, Indonesia simply could not afford to meet these demands without significant changes. Perhaps one of these changes was to save a bit of money and face by ducking out of OPEC, even if it was intended as a temporary measure. Being the odd one out in an organization of net exporters would have made continued membership a contentious decision.

Gabon also tells a story of a country unhappy with the millions of dollars in OPEC fees.[16] OPEC membership costs a flat fee and does not vary based on the size of a country or the amount of oil they produce daily. The country requested to pay lower fees due to its “modest production”, though this proposition was rejected based on the principle of equal voting.[17] Gabon accused OPEC of not taking into account the changing world and limits for each country. Because of this, many of the smaller countries believe they are unfairly hit with a fee that does not guarantee them an equal say, and a consistent criticism levied against the organization is that its policies may end up creating a “large producer’s club”.[18] When Gabon exited OPEC in 1995, they produced less than a twentieth of OPEC’s largest oil producer – Saudi Arabia.[19]

Interestingly, Gabon may have exited OPEC thinking they would be better off going alone, rather than in protest of heavy fees and unequal say. When Ecuador left OPEC in 1992, they attempted to leverage their resources to attract foreign investment. It is possible that Gabon thought they could sell themselves in this way once free from both fees and production quotas.[20] These restrictive production quotas themselves may have been the deciding factor for Gabon.[21] That said, every news story and government press release from Gabon maintains that the primary factor was OPEC’s rejection of the country’s proposal to pay a fee proportional to their oil production.

Why They Chose to Reapply

Two small members of OPEC left. Two small members of OPEC returned. As detailed above, these countries have little in common besides their level of oil exports. Despite this, they share a very similar narrative when it comes to their respective exits of OPEC. High fees and restrictive quotas left both countries feeling as though they would be better off alone. Around the time of Gabon’s (and Ecuador’s) exit from the organization, there were widespread fears of a “better out than in” mentality, whereby other states would follow members out of OPEC.[22] Since the start of this year, those fears have largely been laid to rest. The question remains – why did Indonesia and Gabon return to an organization they accused of unfair fees and more?

Indonesia’s path out of and back into OPEC was decidedly anticlimactic. Upon the exit, the organization said not a word. Even at the time, the Indonesian government made it clear that they would keep the path to reentering OPEC open.[23] The public reasoning behind leaving the organization was a story of high fees and production insufficient to belong to OPEC. Indonesia supposedly was going to push for higher production levels before reconsidering membership.[24] However, the numbers simply do not bear out this strategy; with the exception of 2008, Indonesia significantly reduced the amount of crude oil produced per day in every year since 2007– a trend that began in 1991.[25]

The exact reasons behind this decline are beyond the scope of this project, but the general story is one of government mismanagement and a market not conducive to or attractive for investment.[26] At the same time, Indonesia saw a massive increase in demand for oil, with consumption in thousands of barrels per day almost doubling that being produced.[27] When consumption began to overtake production, the citizens of Indonesia had an interest in low oil prices and this desire only strengthened with a government cutting back on oil subsidies. With the gap between production and consumption at an all-time high, why would Indonesia choose to rejoin an organization largely focused on strengthening the global oil market and keeping prices high enough to support net exporters?

In many ways, Indonesia was in a spot where the benefits of membership outstripped the costs. To this day, the country has little to offer OPEC in terms of production or oil reserves. In fact, the move will likely upset some of the smaller members of the organization, as it takes another slice of their say off the table.[28] Interestingly, the gap between production and consumption that drove Indonesia from OPEC may have reeled them right back in. When the gap was small, membership fees and quotas were cumbersome. Now, demand is so high that the government fears for their own energy security. OPEC stands to gain by bringing in a Southeast Asian nation and Saudi Arabia in particular pushed for Indonesia’s return.[29]

Although it makes little sense for a country interested in low oil prices to join an organization with different intentions, the gap may have grown too extreme for Indonesia to place much stock in OPEC’s intentions. The organization can offer energy security and a seat at the table. However, the island nation sits next to major shipping routes, has a massive population, and skyrocketing demand for oil.[30] In other words, Indonesia can offer OPEC quite a bit, and in return, the country gains a pat on the back and a seat at the table. Being involved in conversations with the organization that controls the vast majority of world oil reserves is too attractive to resist. As such, we conclude that, although Indonesia rejoining OPEC is contradictory to their desire for low oil prices, the offer of membership and its seat at the table is too tempting to decline. Essentially, Indonesia has agreed to pay to sit at a table and be exposed to other members with financial and natural resources, technological information, and some modicum of market control. Does that sound like an honor society?

Interestingly, Gabon expressed the same sentiment of a possible return as Indonesia upon their 1995 exit of the organization.[31] Although they felt they were unduly burdened by fees, the country made sure not to burn any bridges with OPEC. With the nature of their complaint being largely financial, it would follow that Gabon would only rejoin once they were in a position to pay the membership fees, or at such a time as the fees could be renegotiated. Instead, the country seems to have rejoined in a scramble to recoup large budget deficits, with President Ondimba expressing his hope that such a move would help to stabilize oil prices currently hovering around historic lows.[32]

Gabon has found themselves in a difficult position, with revenues highly dependent on oil production and no way to control low prices.[33] Supposedly, they have rejoined in the hopes of an OPEC led effort to increase global oil prices. As we will elaborate in the third blog, global oil price trends show no indication of recovering to the level that countries such as Gabon desire. At first, it was uncertain as to whether OPEC would readmit Gabon, whose production is less than 40% of the second smallest producer in the organization, Ecuador.[34] Ultimately, Gabon was readmitted and the country aims to play a part in realizing OPEC’s desire to increase global oil prices, especially with oil production representing 43% of the country’s GDP.[35]

At first glance, Gabon’s decision is based on sound economic logic, as they are highly dependent on the global price of oil. OPEC seeks to keep the market stable and flex its oil reserves to maintain oil prices at a reasonable level. However, the organization has failed miserably to do so, with Saudi Arabia leading the way in a continuous rise in production and subsequent rock bottom oil prices. With this in mind, what does Gabon stand to gain?

In many ways, the tiny country gains exactly what its much larger OPEC brother, Indonesia, gains. This is little more than a pat on the back and a seat at the table. That said, this particular seat gives Gabon an equal vote in an organization composed of some the most influential countries in the world. Energy security, technology sharing, and some tiny say in the global oil market are worth more than the cost of membership. As in the case of Indonesia, not much has changed in Gabon’s equation since they exited OPEC in 1995. The country faces the same budget deficits and high fees compared to low production that they did years ago.

Conclusion

Despite multiple exits, membership in The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries currently stands at fourteen members. This number includes every single member that has ever left the organization. In the case of Gabon and Indonesia, leaving the organization did not better their lot in the global oil market. Both countries still face deficits and are struggling with low oil prices. At first it sounds laughable to compare OPEC with an honor society, but in many ways, the decision faced by Gabon and Indonesia parallels my own decision on whether or not to pay fees for any number of honor societies that send me letters or emails. I have to decide whether cutting into my depressing, college student bank account is worth the benefits of membership. This membership is something I can place on a resume, gives me some say in the actions of the group, and has the potential to introduce me to new ideas, influential people, and help improve my academic abilities. Gabon and Indonesia decided to pay their fees and we would suggest they did not do so in the vain hope of increasing global oil prices, just as I would not join an honors society to land a better salary. Instead, they joined for a seat at the table, technology sharing, and some level of energy security based on their connections within OPEC. Is OPEC an honors society?

[1] “Member Countries”

[2] “OPEC Share of World Crude Oil Reserves.”

[3] The World Factbook: Indonesia

[4] Ibid.

[5] The World Factbook: Gabon

[6-9] Ibid.

[10-12] “Indonesia Leaves OPEC, Unhappy with Influential Power.”

[13] “Indonesia Pulls out of OPEC.”

[14-15] “Indonesia Leaves OPEC, Unhappy with Influential Power.”

[16] “Gabon Protests OPEC Fee; Withdrawal Reported.”

[19-20] “Gabon Protests OPEC Fee; Withdrawal Reported.”

[21-22] “Gabon Leaves OPEC: Membership Reduced to 11.”

[17] “Gabon Plans To Quit OPEC.”[18] “Gabon Leaves OPEC: Membership Reduced to 11.”

[23] “Indonesia to Withdraw from Opec.”

[24] “Indonesia Leaves OPEC, Unhappy with Influential Power.”

[25] “Indonesia Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year.”

[26-27] “Crude Oil.”

[28-30] Berndt, Kirstin. “And Then There Were 13: Indonesia Rejoins OPEC.”

[31] “Gabon Leaves OPEC: Membership Reduced to 11.”

[32-33] Salvaterra, Neanda. “Gabon – At A Glance.”

[34-35] “Another Former OPEC Member, Gabon, Wants to Rejoin Oil Group: Sources.”

Works Cited:

Aglionby, John. “Indonesia Pulls out of Opec.” Financial Times. May 28, 2008. Accessed July 2016. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/d0e346fe-2c87-11dd-88c6000077b07658.html#axzz4FYj93hvP.

Berndt, Kirstin. “And Then There Were 13: Indonesia Rejoins OPEC.” The Diplomat. December 2, 2015. Accessed July 2016. http://thediplomat.com/2015/12/and-then-there-were-13-indonesia-rejoins-opec/.

“Crude Oil.” Indonesia Investments. July 4, 2016. Accessed July 2016. http://www.indonesia-investments.com/business/commodities/crude-oil/item267.

El Gamal, Rania, and Alex Lawler. “Another Former OPEC Member, Gabon, Wants to Rejoin Oil Group: Sources.” Reuters. April 15, 2016. Accessed July 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-gabon-opec-idUSKCN0XC0HZ.

“Gabon Leaves OPEC: Membership Reduced to 11.” MEES. January 9, 1995. Accessed July 2016. https://mees.com/opec-history/1995/01/09/gabon-leaves-opec-membership-reduced-to-11/.

“Gabon Plans To Quit OPEC.” The New York Times. January 9, 1995. Accessed July 2016. http://www.nytimes.com/1995/01/09/business/gabon-plans-to-quit-opec.html.

“Gabon Protests OPEC Fee; Withdrawal Reported.” Oil & Gas Journal. January 16, 1995. Accessed July 2016. http://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-93/issue-3/in-this-issue/general-interest/gabon-protests-opec-fee-withdrawal-reported.html

“Indonesia Crude Oil Production and Consumption by Year.” IndexMundi. 2016. Accessed July 2016. http://www.indexmundi.com/energy/?country=id.

“Indonesia Leaves OPEC, Unhappy with Influential Power.” Oil & Gas Journal. June 2, 2008. Accessed July 2016. http://www.ogj.com/articles/print/volume-106/issue-21/general-interest/indonesia-leaves-opec-unhappy-with-influential-power.html.

“Indonesia to Withdraw from Opec.” BBC News. May 28, 2008. Accessed July 2016. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/business/7423008.stm.

“Member Countries.” Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. 2016. Accessed July 2016. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/about_us/25.htm.

“OPEC Share of World Crude Oil Reserves.” Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries. 2015. Accessed July 2016. http://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/data_graphs/330.htm.

Salvaterra, Neanda. “Gabon – At A Glance.” The Wall Street Journal. June 2, 2016. Accessed July 2016. http://blogs.wsj.com/briefly/2016/06/02/gabon-at-a-glance/.

“The World Factbook: Gabon.” Central Intelligence Agency. 2016. Accessed July 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/gb.html

“The World Factbook: Indonesia.” Central Intelligence Agency. 2016. Accessed July 2016. https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/id.html.

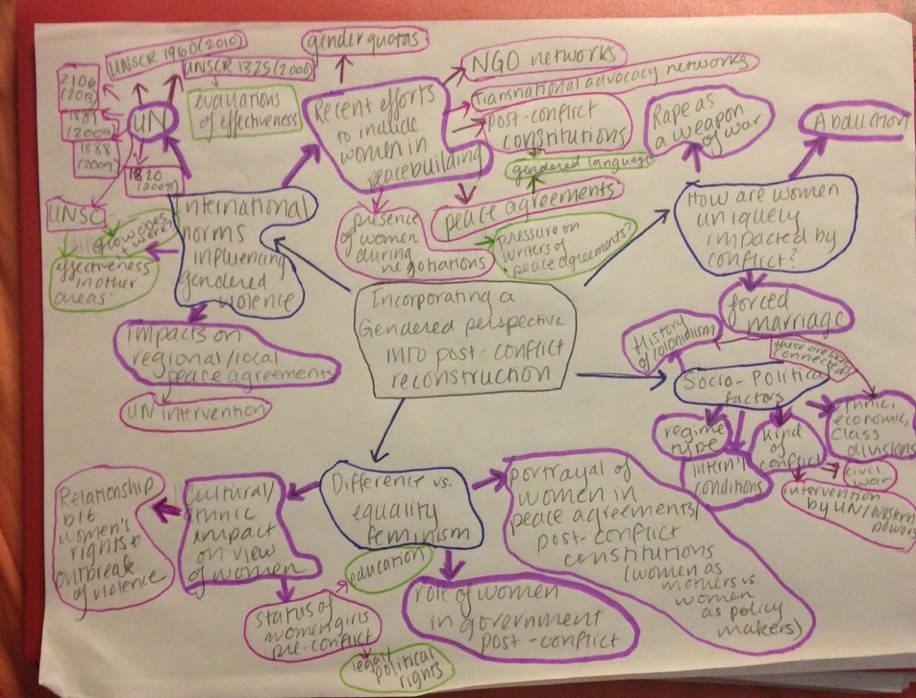

This brings us to this semester, spring of 2016. Professor Holmes and I were lucky enough to receive a proof of Dr. Allan and Dr. Bentley’s upcoming book on national identity. In the proof, they listed a brief process of coding national identity and a chapter on their analysis of Japanese national identity. Their method of coding does not consist of a list of categories but rather three ways to approach topics: valence, aspirational versus aversive, and significant others. Valence assess whether or not the identity is a good or bad feature. Aspiration versus aversive is a comparative measure in whether or not the feature is something to strive for or avoid. Lastly, significant other is another comparative assessment in who or what they are measuring up with. All three of these topics can be used together to create a national identity category.

This brings us to this semester, spring of 2016. Professor Holmes and I were lucky enough to receive a proof of Dr. Allan and Dr. Bentley’s upcoming book on national identity. In the proof, they listed a brief process of coding national identity and a chapter on their analysis of Japanese national identity. Their method of coding does not consist of a list of categories but rather three ways to approach topics: valence, aspirational versus aversive, and significant others. Valence assess whether or not the identity is a good or bad feature. Aspiration versus aversive is a comparative measure in whether or not the feature is something to strive for or avoid. Lastly, significant other is another comparative assessment in who or what they are measuring up with. All three of these topics can be used together to create a national identity category.

We set out to discover how a local police force, protecting a small town of twenty-one thousand residents could purchase, pay for, and protect military grade weaponry.

We set out to discover how a local police force, protecting a small town of twenty-one thousand residents could purchase, pay for, and protect military grade weaponry.